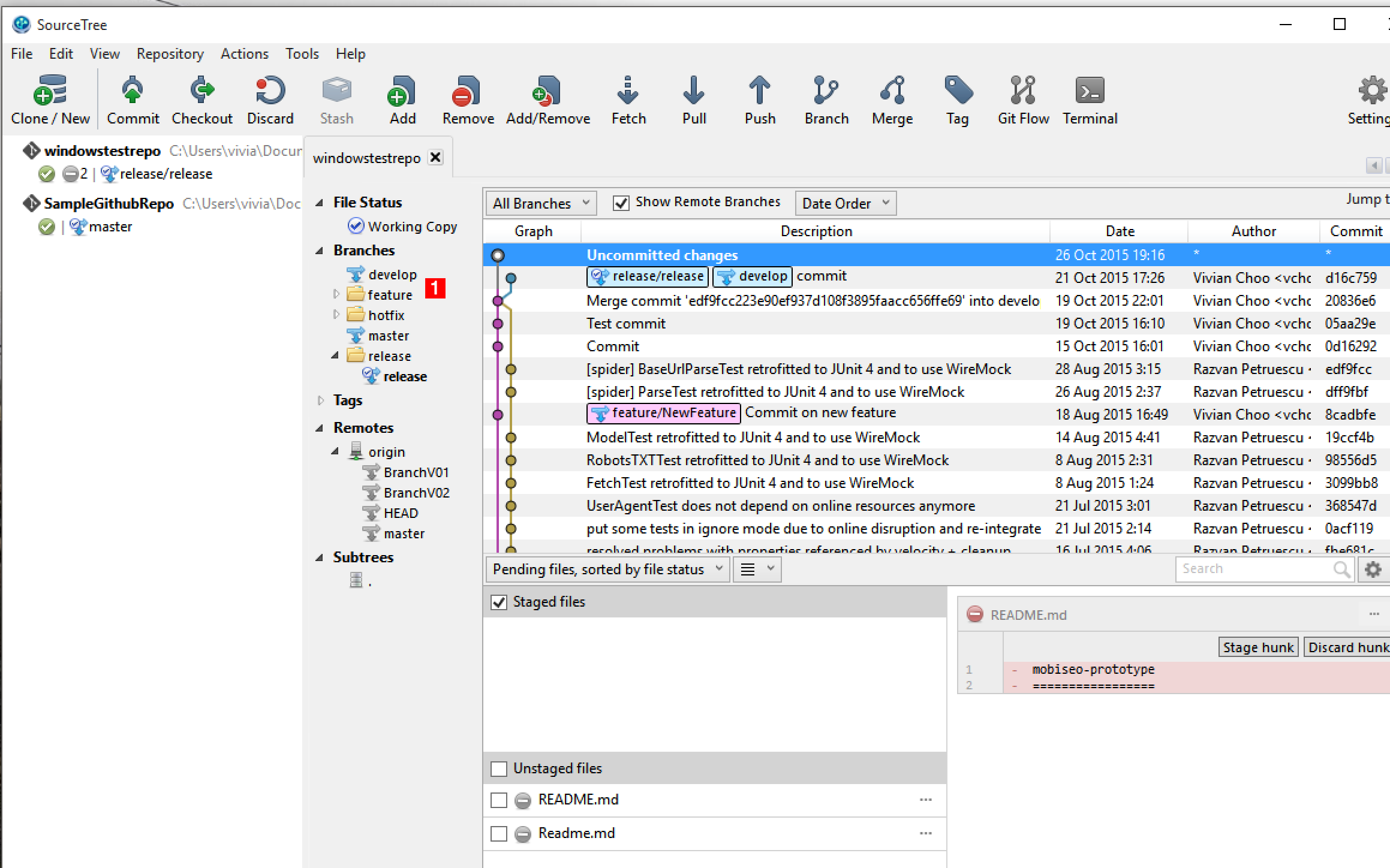

How do I checkout a remote branch?Ī remote branch is the best way to share your development work with other people in your team. It totally makes sense to do this in a separate level branch that originates from your feature branch. This might sound weird, but imagine you are creating a new feature in a new branch and you want to experiment a bit. Knowing this, you can also make a branch from a branch recursively. Note: when you check out a branch on your local machine, all commits will be on the new branch and not on the main. If you want to work in this branch and commit to it, you need to check out this branch just like before using git checkout dev. When you want to create a new branch from your main branch with the name “dev”, for example, use git branch dev-this only creates the branch. The DWIM mode won't work because git checkout develop doesn't know whether to use origin/develop or upstream/develop.If you already have a branch on your local machine, you can simply check out or switch to that branch using the command git checkout. It's useful if you have no develop right now, but do have both origin/develop and upstream/develop. This looks up the remote-tracking name, then uses it to create a new (local) branch using the same name: in this case it would create a new branch develop, as if you'd run git checkout -b develop upstream/develop. (See Checkout another branch when there are uncommitted changes on the current branch for more about when you can or cannot switch to another commit.)įor completeness, we should also mention git checkout -track remote-tracking name, e.g., git checkout -track upstream/develop.

This fails if the name exists or if you can't git checkout that particular commit hash ID right now. Git checkout -b name commit-specifier-which you can invoke manually if you like, but is invoked for you by the DWIM mode-tries to create a new branch name name, using the given commit-specifier as the hash ID for the new branch. Which as you can see has one more argument than the original -b option. Git checkout -b name remote-tracking-name If exactly one matches, it performs the equivalent of: The DWIM step checks all of your remote-tracking names: origin/ name, upstream/ name if you have a remote named upstream, and so on. If that fails because name does not exist, it goes on to a second step, which Git documentation sometimes calls the "DWIM" mode: Do What I Mean. Git checkout name tries to check out an existing branch using the name name. This fails if the branch name already exists. Git checkout -b name tries to create a new branch name name, using the current (HEAD) commit as the hash ID for the new branch. Git diff upstream/branch2 branch2 # should be like diffing branch1 and upstream/branch2Ĭaleb's answer is correct (and I've upvoted it) but here it is in more precise notation: Verify: git diff upstream/branch1 branch2 # should be no diffs Now you should have a local branch2, but it should match what's in branch1 and also upstream/branch1. Next, try creating a branch2 using the -b flag: git checkout -b branch2 Again, check that this matches the upstream version: git diff upstream/branch1 branch1. Now you should have a local branch called branch1. Now checkout the first branch without the -b flag: git checkout branch1 Verify that there are differences with git diff upstream/branch1 upstream/branch2. Just pick two existing remote branches that don't exist locally, say upstream/branch1 and upstream/branch2 on your remote that you know have some differences. Will report the differences between upstream's bar branch and your local bar branch (which, again, got its content from your foo branch). Then git will create a new branch that happens to also be named bar, but that will have the same content as the foo branch that you were just in. In other words, if you do: git diff upstream/barīut, if you give the -b flag: git checkout -b bar Then you'll switch to a local copy of the foo branch on upstream (assuming your repo already knows about foo because you've recently done a git fetch). So, let's say: 1) you're currently in your own branch called foo 2) you've got a remote called upstream and 3) that remote has a branch called bar. Without the flag, git will look for an existing branch, including one in any remote repos that you're tracking, and switch to one of those if if finds one. The difference is that if you pass the -b flag, git creates a new branch with the name you give and based on the branch you were in when you created that branch. In this case, when do I have to pass the -b parameter? What is the difference between the below when the remote does exist

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)